Digital Affective Spaces and the Black Lives Matter Movement

by Leon Hughes

Erica Baffelli and Frederik Schröer, writing their Feeling News post over three months ago, rightly noted that COVID had created equally a spatial and a temporal absence. National lockdowns had both regulated and restricted space and established an infinite temporal horizon. However, what Baffelli and Schröer failed to mention was that as we have withdrawn from our physical lived spaces, our schools, universities, shops and public transport, digital space has expanded in use. That is not to say that COVID brought about this movement, but until March of this year, one used physical and digital space concomitantly. The last few months have seen the digital privileged.

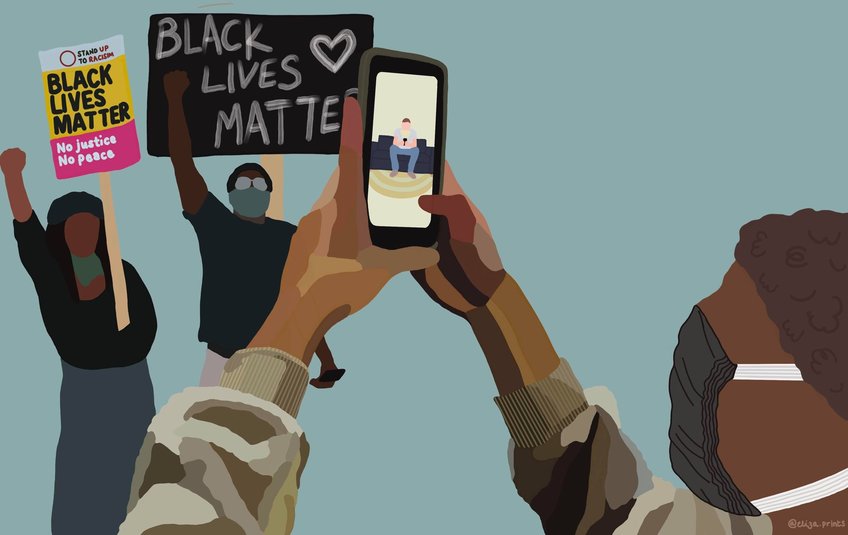

The privileging of the digital has obviously had a great impact upon our lived experiences as work, socialising, even exercise have moved online. However, the eruption of the Black Lives Matter protests in America, and their spread to Paris, London, Buenos Aires, among many other global cities, demonstrated how the absence Baffelli and Schröder identified, has turned into collective action. This collective activism has been enabled by social media, with a recognition of how the use of digital affective spaces can galvanise feeling and connectedness in disparate, heterogenous global communities. Digital media enabled this phenomenon as both space and time are truncated to connect an increasingly globalised world around the social issues identified by the Black Lives Matter movement.

However, this is not the first time that social media has triggered social action. In the Arab Spring of 2011, a new concept of revolution arose – Revolution 2.0. The term was coined by Wael Ghonim, the Facebook admin of the page ‘We Are All Khaled Said’, who distributed images of his government’s atrocities against the Egyptian people. Ghonim argued that social media is a tool to educate a vast network of people to the horrors and atrocities that are lived realities to a certain societal group but can remain unobserved to those outside this group. This digital coordination has further precedent in the use of Twitter in the Iranian Green Revolution of 2009 and the 2020 Belarus protests, coordinated by the messaging app ‘Telegram’, to circumnavigate Alexander Lukashenko’s media black-out. However, these are all political revolutions, with discrete populations living in a national context with each other. The Black Lives Matter protest is a social revolution, with a much larger affective potential due to the African diaspora, and transnational extent of the systemic racism highlighted by the killing of George Floyd.

Digital Affective Spaces

COVID has hence created a context whereby digital spaces are increasing in use, yet one must ask, how has this digital expansion affected how we feel? Digital technology holds huge affective potential; it can be described as ‘emotional media’ (Tettegah, 2016). This is because social media is participatory; users must engage with others through an ‘emotional architecture’ (Serrano-Puche, 2015). Actions such as ‘liking’, ‘sharing’, ‘retweeting’, ‘reacting’ all express emotional reaction, personalising digital spaces and necessarily imbuing digital content with feeling. This emotional reaction, as well as the ability to talk to other users and join affiliate groups, enables an ‘affective public’ to be formed (Serrano-Puche, 2015).

An ‘affective public’ is one predicated upon a space where online discourse and alignment can be formed around mediated digital interaction (Papacharissi, 2016; 2014). This digital alignment can be formed, not through physical activism like attending a demonstration, but digital signifiers such as hashtags or the Instagram black squares of ‘Black Out Tuesday’. In the case of Breonna Taylor, the digital signifiers which have allowed an affective public to be formed range from hashtags such as #SayHerName and #JusticeforBre and the late-June viral chain tweeting ‘Breonna Taylor’s name is no longer trending and the police that murdered her are still free’. These signifiers arose next to a multitude of digital petitions, as well as the circulation of the phone numbers of Public Integrity Department of the Louisville Metro Police Department and the Kentucky Attorney General. The use of such directions for collective action mediated a connectedness and belonging in these digital spaces.

Relational Scenarios and Hegemonic Contestation

Emotions are context dependent, with their emergence via digital stimuli based upon ‘relational scenarios’ (Burkitt, 2014). The power of the BLM movement is its ubiquity; resultant from the police violence and systemic racism which remains an insidious feature of America, the UK and France, to name a few countries where BLM protests took place. This relational aspect of the events taking place in America was sustained and then exacerbated by the architecture of social media. Through the ability to repost videos, infographics, posts of solidarity, often with a comment based on an individual’s own experience, the participatory aspect of social media personalised and contextualised the events in America to different national, and local, scenarios.

The relational scenarios afforded by the BLM protestors are intimately connected to the different levels of digital affect cultures – cultural practices people do to mediate emotion online. These can occur at micro, meso or macro levels, or at personal, group or global levels, with the BLM protests operating at all three. However, the BLM were given such large affective potential through the interaction between all three, specifically how micro, personalised narratives, were picked up and transmitted globally, at the macro level.

A principle method of this micro reportage of the protests was through recorded videos. This is an emerging phenomena whereby modern individuals believe their most effective defence from danger is recording incidents on their smartphone (Cumiskey and Brewster, 2012). This creates a reportage much more reactive and personal. When one considers notions of digital embodiment, this hence holds much larger affective potential for digital audiences as the individual recording the event is not a neutral professional reporter, but an actual embodied participant.

Moreover, as individuals post these videos on their own personal social media accounts, a bond of intimacy is again formed as the individual inhabits a digital space, as well as the physical one relayed in the video. One can see their social media account, going back to when they had not participated in the riot, reading posts, tweets, seeing pictures of an individuals’ life lived in relative normality. Due to the archival feature of social media, one can chronologically see when their life was dislocated by their presence in the BLM riots. This forms a personalised narrative in which the effect of the protests is increased in proportion through the juxtaposition to a life lived before the protest.

The distribution of such videos, on social media such as Twitter and Facebook, allow such movements to contest the hegemonic presentation of events normatively labelled as anti-order, such as demonstrations. As Manuel Castells’ has argued, empowerment is control over communication (Castells, 2004). To Castells, social media promotes cultural diversity and certain freedoms, to such a degree that hegemonic regimes can be contested digitally. The normative presentation of social protests revolves around statistic heavy recording of numbers or infographics to show regional distribution, often with a few considered and calm interviews afterwards. The use of social media directly counters these methods of protest reportage and enables the scaling of social movements as one can identify much more personally and empathetically with participants (Mundt, Ross and Burnett, 2018).

A Precedent Set?

Hence one must ask what the implications of digital affective spaces for the future of social movements are. Here lies my partial answer to Keith Baker and Dan Edelstein’s question ‘has Facebook revolutionised revolution?’ (Baker and Edelstein, 2015). The Black Lives Matter protests, following Wael Ghonim and the Iranian Green Movement, demonstrates the affective potential of participatory social media to form digital spaces which create conditions to coordinate localised social action. This action is predicated upon empathy. Empathy towards a cause which can be witnessed, felt, and then acted upon. The rise of digital media in a social movement such as Black Lives Matters gives it fundamentally more affective scope and potential.