Order through disorder: Complexity as central for the human brain

New findings on the organizational principles of spontaneous brain activity – the "complexome"

Researchers from Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research report new findings on the organizational principles of spontaneous brain activity – the "complexome". They present their findings in the journal Science Advances.

The human brain works via large-scale functional networks. How the activity patterns of individual brain regions are related to the network structure of the brain as a whole is not yet fully understood. Scientists at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development have now taken an important step forward. To isolate the underlying organizational principles of the brain, they studied the spontaneous brain activity of 343 healthy adults from the Human Connectome Project across two time points. Brain signals were recorded using functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Using a special “complexity” analysis that captures the repetition of patterns of brain activity, the authors were able to identify features of brain activity that are not detected by conventional methods.

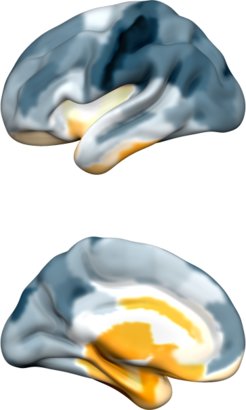

The authors demonstrated that the brain operates in different states of complexity, which explain important network properties. “Specifically, we show that brain activity is highly irregular most of the time, which is reflected by a high degree of complexity. However, this “default state” is recurrently interrupted by spontaneous episodes of low complexity (“complexity drops”), in which brain activity becomes much more regular for a short moment in time,” writes Stephan Krohn, a scientist at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin (see New findings on brain networks: Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin (charite.de)). These complexity drops largely accounted for how brain regions interacted with one another from moment-to-moment. Surprisingly, this complexity pattern could be detected in each of the almost 700 MRIs examined. This points to a very fundamental organizational principle of how activity within a brain region drives brain network communication, which can be summarised as the human "complexome".

Age also had a strong influence on these activity patterns; the researchers found that lower complexity was associated with younger age and better cognitive and motor performance. They view this as a sign that a higher capacity for complexity drops can be a behaviourally relevant and beneficial aspect of brain function.

Central ideas of the present study trace back to the previous work of Max Planck UCL Centre scientists on the complexity of neural activity (e.g., Waschke et al., 2021, Neuron). "Human and animal behaviour is highly malleable, successfully adapting to internal and external demands. Such behavioural success is in striking contrast to the apparent instability of neuronal activity or its variability," explains study co-author Leonhard Waschke from The Lifespan Neural Dynamics Group (LNDG) at the Max Planck UCL Centre for Psychiatry and Ageing Research. "We believe that only by including this variability can the neural basis of behaviour be comprehensively understood," he continues.