Emotions in German Penal Law

(1794-1945)

Ute Frevert

The issue of penal law - its theoretical underpinnings and how it is put into (social) practice - is particularly fascinating and instructive for historians of emotions, especially with regard to the so-called crimes of passion and crimes of honour (including insults and affronts). Both categories have been perceived and treated as criminal acts motivated by emotions (affects, passions, feelings, aggravation).

Generations of legal experts and professionals have tackled questions such as:

- How were those emotions triggered?

- What impact did they have on the person(s) in concern?

- To what extent did they reduce their free will, sanity and responsibility?

- Were persons in concern expected to fight those emotions and return to a ‘"reasonable" state of mind?

- What kind of emotions were involved and how should they be morally judged?

- Who was more susceptible or resilient to becoming emotionally overwhelmed?

Such contemplations were guided by legal traditions and doctrines, but they were also informed by psychological and medical opinion, and they usually aimed to reflect wider contemporary perceptions and attitudes. At the same time, they were by no means purely theoretical. Instead, they had strong repercussions on the way in which justice was administered, defendants mounted their defense, and the public commented on the case.

The research project scrutinizes the ways in which emotions were perceived and handled by those who drafted legal codes and administered justice in Germany between 1794 and 1945. Law continuously struggled to make sense of emotions, striving to relate them to paramount categories of free will, individual responsibility and culpability. Legal debates thus offer fascinating insights into contemporary discourses on reason and affect, good and bad morals, ‘cool’ and ‘hot blood’, fair-unfair/likeable-despicable emotions. They also contribute to social and gender stereotyping, although often against current trends: By constructing the passionate man as opposed to the premeditating woman, they undermine traditional nineteenth-century ideas about gender or at least add new, influential facets to contemporary gender discourses.

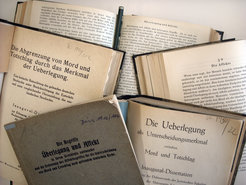

Sources to be examined include legal drafts, commentaries and scholarly contributions (of which there are plenty), as well as trial records. Trials concerning so-called crimes of passion as well as crimes of honor put emotions center-stage and offer historians a rare opportunity to see passions at work on different sides of the courtroom.