Emotional Transitions

Religious and Non-Religious Emotions in North India, ca. 1840-1920

Max Stille (project duration 2017-2019)

We all know which emotion belongs to which place and space: religious emotions to holy places or religious feasts, excitement to crime stories, contemplation to museums. And we know what it is like when we leave the museum, the church or the mosque, or lay the book aside – the emotions remain or evaporate, grow stronger or weaker, or superimpose themselves. We know all this because we have learned to control emotions, to transfer them, set them in context. And to do this, we rely on societal conventions, which are, in turn, subject to historical change.

This project examines how humans adopt emotions in one area of experience and transpose them on to another. How do historical actors discuss or practice such transitions? Are there emotions which are specifically progressive, specifically religious or specifically literary? Or are there even emotions which are specifically Muslim, specifically mystical, specifically poetic. How do humans react emotionally to societal differentiation, new media and conceptual spaces?

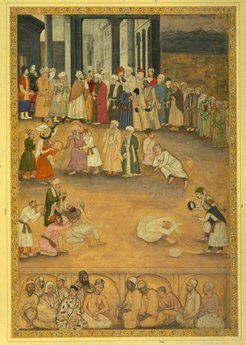

In North India during the period under consideration, areas of experience were shifting and new ones were created. Media and spaces changed drastically. Educational and missionary movements acting transregionally enabled religion to become a matter of public discussion outside of academic circles, and made it the basis of identity for societal groups. This correlated with an increasing separation of "Indian" and "colonial" areas. The boundaries between groups and philosophies were discussed in newly created newspapers and magazines, as well as in early novels and biographies. Writers created characters that showed the characteristics of their own group, mediated between the various areas or pragmatically worked on themselves to survive in a world that was perceived as new.

Religious and emotional education played a large role in the discussions of contemporary Muslim social reformers. They asked how new and newly perceived media, from religious speech to literature, could influence society and questioned the earlier limitations of religious and literary experience. At the same time, there was an orientation towards ‘reality’ that devaluated other areas of experience. However, this sort of hierarchical systemizing and naturalizing areas of emotions often remained theoretical, while literary and religious practice absorbed and passed on a variety of models which were based on discontinuous/intermittent spaces: piety in daily life still encompassed miracles, and the poetic emotions continued to figure prominently in the production and reception of literature.

Historicizing emotional transitions offers the chance to complicate existing master narratives of modernity. The questions posed here highlight the possible fragmentation of the individual through a multiplication of areas of experience. They therefore enable a historical understanding of the current challenges of a world which is once again faced with a surge of new media and changing spaces.