How judgments propagate

People frequently rely on others to form judgments and make decisions. Whether people are judging the quality of a rock band, evaluating the risks of a vaccine, or choosing a president, the influence of the social environment is omnipresent. In recent research, we have discovered that social influence is not limited to one’s friends and acquaintances: Judgments can travel from person to person, much like the common cold.

From Paul to John to Ringo

Consider, for instance, John and Paul. John has noticed that his friend Paul often has good advice about leading a healthy lifestyle. Over time, John has learned to follow Paul’s recommendations. John’s behavior can therefore be understood in large part by considering Paul’s judgment. But where does Paul’s judgment come from? It turns out that Paul’s wife, Georgia, is a nutritionist. Thus, Georgia’s health expertise impacts John’s behavior, even though John and Georgia do not know each other. In this example, Georgia, Paul, and John form a transmission chain—a social pathway that conveys judgments and behaviors. Transmission chains do not need to be limited to three individuals. For instance, John may also discuss his healthy lifestyle with his colleague Ringo, who may in turn mention it to his wife Lucy, thus extending Georgia’s range of influence.

What are the features of such long-range social influence? Can Georgia really have a substantial impact on the behavior of her husband’s friend’s colleague’s wife? In sum, what collective dynamics drive people’s judgments and decision making?

Propagation waves

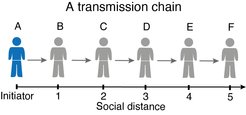

We conducted an experiment to study how far long-range influence can extend. We created transmission chains of 6 participants who had to determine the main direction of movement of a set of dots on a computer screen. In addition to the visual stimuli, each person in the chain could also see the answer of the preceding person: The judgment of the initiator of the chain (Individual A) was observed by the next participant (Individual B), who was in turn observed by the next participant (Individual C), and so forth until the end of the chain (Individual F). We were able to track the influence of Individual A on the judgment of all the subsequent individuals in the chain.

Round after round, we observed that Individual A’s judgment started to travel down the chain, first influencing Individual B, who in turn influenced Individual C and so forth. However, these “waves'' of judgment propagation stopped beyond a social horizon located three persons away from the initiator. That is, the judgment of Individual A had a substantial impact on the judgments of Individuals B, C, and D, but not on Individuals E and F. This “propagation wall” is partly due to information distortion: The influence of the initial judgment tends to deteriorate over social transmissions. By the time Individual A’s judgment had reached individual E, it was no longer convincing enough to be adopted.

Information distortion

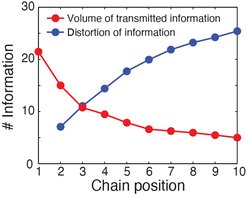

Information distortion is key to understanding judgment propagation. In another experiment, we studied social contagion in the domain of risk perception. We created transmission chains of 10 participants. The first person in the chain read a document describing the risks and benefits of a controversial antibacterial agent found in many consumer products. This person then had to report on it to the next individual in the chain, who in turn passed the information to the next individual, and so forth until the end of the chain.

We found that the content of the message underwent strong distortions as it moved down the chain, becoming simplistic, incomplete, and mostly incorrect when it reached the last participant. Remarkably, this distortion was not random—the message always changed to fit the risk perception of the person who communicated it. Participants who were initially concerned about the risk tended to exaggerate the possible dangers of the antibacterial agent, whereas those who were not concerned tended to downplay the risk. When information is shared in groups of like-minded people, as is often the case on social media, this bias can cause prejudicial amplification loops: The message becomes more extreme, thereby reinforcing the judgment of the group members who further amplify the message—and ultimately polarizing risk attitudes.

Our research shows that, like infectious diseases, judgment can propagate from person to person and even mutate during the transmission. Understanding the social mechanisms of judgment formation is key to implementing efficient behavioral intervention campaigns. Our models could help health managers predict how far a given judgment will spread in the population (e.g., the anti-vaccination movement) and how to efficiently communicate with polarized groups. This is all the more important in the context of the COVID-19 health crisis.

References

- Moussaïd, M., Brighton, H., & Gaissmaier, W. (2015). The amplification of risk in experimental diffusion chains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(18), 5631–5636.

- Moussaïd, M., Herzog, S. M., Kämmer, J. E., & Hertwig, R. (2017). Reach and speed of judgment propagation in the laboratory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(16), 4117–4122.