“Nothing Spreads Like Fear”: On Plague Parallels in Defoe and the Corona Crisis

by Kerstin Maria Pahl

The pedestrian felt uncomfortable: "it was a most surprising thing, to see those Streets, which were usually so thronged, now grown desolate". However, since the disease had not yet spread to all parts of the city, people were "allarm’d, and unallarm’d again, till it began to be familiar to them" and, eventually, they "began to take Courage and to be, as I may say, a little hardened."

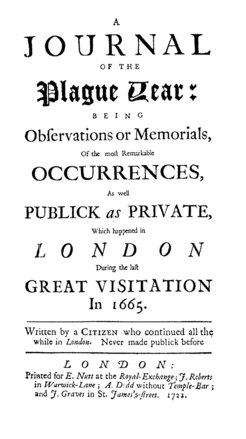

The streets are in London, the year is 1665. The narrator of A Journal of the Plague Year stays behind in a city that slowly empties out. It’s getting warmer, the disease spreads. Infected houses are shuttered, people turn to religion and superstition, can’t distinguish between sound medical advice (self-isolate) and quackery (pills made of mercury), and are susceptible to conspiracy and theories. Afraid of the illness, but trusting in providence and reason, the narrator sees panic and irrationality, but also indifference, indulgence, righteousness, and devil-may-care attitudes proliferate. But the overwhelming emotion is, unsurprisingly, fear in all its shades: angst, anxiety, fright, despair, dread, terror. People are afraid of dying, of pain and suffering, anxious about money and property, about unconfessed deeds and salvation: “there was a great deal of Alarm, sounded into the very inmost soul”.

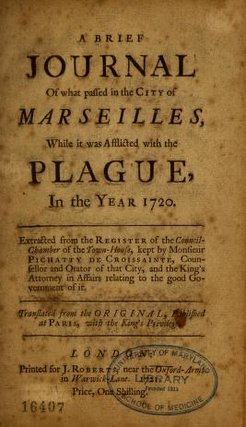

The Journal poses as an eye-witness account, but it is, in fact, a fictional work, published by Daniel Defoe in 1722. It was, however, topical: in 1720, the plague had reached Marseille, and Britons were apprehensive lest it come to their country. Accordingly, Defoe’s work mirrored books like A brief Journal of what passed in the City of Marseille While It Was Afflicted with the Plague of 1720 (fig. 1, 2). Extensive use of the original 1665 "Bills of Mortality", i.e., statistics that listed number and causes of death, and official orders, commanding the sick to be isolated and the healthy to not gather in public, lent it authenticity and urgency. Dry data made the narrative exciting.

Besides the mortality rates, regulations and behaviours, emotions seemed to resonate eerily over the decades and over land and sea. The fear of illness in 1665, the narrative implied, was the same as it was in 1722. Defoe teased out similarities between the historic plague and the contemporary disease, but it is, and necessarily so, full of passages which the corona crisis almost three centuries later seems to echo: vacated places, the sequestering of the infected, suspension of public gatherings, fear for one’s life, compassion, hope, and dispute over the best course of action.

In the current media coverage of corona, historical and fictional parallels abound. The Spanish Flu, which killed an estimated 30 to 50 million people between 1918 and 1920, has served as a point of reference from the outset, as has the movie Contagion (USA 2011), which became one of the most watched flicks in March 2020. "‘Contagion’ vs. coronavirus: The film’s connections to a real life pandemic", ran a CNN headline. As soon as the first wave of analogies had subsided, a second strand of argumentation emerged, its thrust being a warning against simplified analogies that try to transpose historical or fictional events to contemporary situations. Is it fruitful to hark back to diseases past and find commonalities, although the only way forward should always be, well, forward? Are there lessons to be gleaned from comparisons and similes, whether historical or fictional ones?

Regardless, however, of the plausibility of disease compilations and the reductive treatment of literary or visual narratives it entails, there seems to be a need for them. Be it Defoe in 1722, or movie viewers in 2020, people look for foils, templates, models, and patterns. They seek out unsettling resemblances in history and fiction, both indulging in and exorcising fear by engaging with it in a relatively safe environment. It is not only illness, but also the quest for comparisons that transcends the centuries. The entertainment website TheWrap listed, for example, 20 "very cathartic movies about virus outbreaks to get you through it".

Indeed, since Aristotle’s Poetic theory has expounded on the liberating and redemptive, and therefore cathartic, effect of experiencing fear and pity in art, and explained how non-real life renderings serve as emotional training grounds to hone both intellect and feelings. A historical case or a narrative contains the malady for now, exemplifying what could be, but is not (yet).

Sickness engenders fear, but, most of all, Defoe and Contagion express the fear of fear. The movie’s subtitle, "Nothing spreads like fear", indicates that infection extends beyond germs and viruses and bacteria – an idea well known to Defoe’s contemporaries. "From look to look," the poet James Thomson wrote in 1730, "contagious thro’ the crowd, The Pannic runs" (The Seasons, “Autumn”). Fear drowns out other emotions; fear catalyzes inhuman conduct: "There is no Pity stirring in the Time of a Plague, the Fear of catching the Contagion stifles all Sentiments of Charity, and even those of Humanity", stated the "Brief Journal" on the Marseille Plague of 1720.

At first glance, social behaviour during the corona crisis could not have done better at dispelling this fear. The media has been full of appeals to solidarity, community, and care, and these have been heeded. #SocialDistancingNow became the rallying cry, and most followed. Still, those repeated pleas and overt (if not sometimes ostentatious) testimonies to togetherness show that the sword of Damocles, dangling over societies during times of diseases, is still social disintegration and the collapse of community, institutions, order.

What purpose, then, do plague parallels serve? Maybe it is less about lessons and learning than about calm and consolation. Parallels attest to the persistent desire for parallels in the first place to show fears and hopes that have already been feared and hoped. Through his narrative, Defoe made a historic plague relatable in a double sense: empathetically understandable as well as tellable; both are necessary for their eventual function. Such analogous narratives, which illustrate that neither events nor emotions are unprecedented, provide safe spaces for undergoing emotional experiences in unsafe times.