Ecological Learning: Selecting the Most Efficient Active Learning Strategies

Active learning strategies cannot be defined as optimal in absolute terms. Instead, their efficiency depends on children’s prior knowledge and expectations, as well as on the task’s information structure, that is, the number of hypotheses available and their likelihood.

Ecological learning is a research framework that considers for the first time both children’s cognitive development as well as the characteristics of their learning environment. Ecological learning studies how children learn by exploiting the ecology, the particular structure and characteristics of a learning environment. To exploit the ecology of a certain environment, a child needs to detect its characteristics and dynamically adapt the learning strategies to those characteristics, to achieve effectiveness.

For example, yesterday Toma was late for school. Why was Toma late for school? Let’s suppose we have these 4 possible reasons for Toma being late for school.

These hypotheses are known to be equally likely to be correct. You have to find why Toma was late for school in as few questions as possible. What would you ask?

For example, you could ask whether Toma was late because of something he could not find. This is a good question, because whatever the answer is - yes or no - you will be able to rule out two of the four hypotheses. This type of question is called constraint-seeking. Constraint-seeking questions aim at reducing the space of possible hypotheses by testing features shared by several hypotheses.

Now, let’s suppose we have again those 4 possible reasons for Toma being late for school. But this time they are not all equally likely to be correct: Toma being late for school because he woke up late is the most likely hypothesis. Would you ask the same question? Or would you maybe ask whether Toma is late because he woke up late? You can see that this question now seems more attractive - although it targets only one hypothesis, it offers the opportunity for a quick win. This type of question is called hypothesis-scanning.

Because constraint-seeking questions are able to rule out multiple hypotheses at each step of the search process, they are traditionally considered better than hypothesis-scanning questions. However, as you have seen in the example above, this is not always the case. The iSearch research program considers how the traditional distinction between different question types, or more generally, between different explorative actions, maps onto the more formal distinction between more and less informative actions, depending on the information structure of the problem being considered. With this ecological learning perspective, we have provided the first evidence to demonstrate that 5- to 10-year-olds and young adults change the types of questions they rely on in response to the information structure of the task (Ruggeri & Lombrozo, 2015; Ruggeri, Sim, & Xu, 2017). Despite the general developmental increase in performance, our work shows that children adapt their active learning strategies as or even more promptly than adults (Ruggeri & Lombrozo, 2015).

One of Our Ecological Learning projects: BOXES

In the BOXES study we investigate whether 3- to 5-year-olds adapt their exploratory actions to different information structures (i.e., distribution of likelihood across different hypotheses) of the environment. The experimental session involves a training and a test phase.

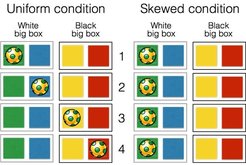

Training phase. Participants are presented with two big boxes, each containing two smaller boxes. The experimenter places an egg shaker in one of the small boxes, four times. Children will be assigned to one of two experimental conditions: In the uniform condition the experimenter always places the egg in a different small box; in the skewed condition she always places the egg in the same small box.

After each placement, children are asked to retrieve the egg and use it to activate a machine that makes music. Children are then demonstrated two actions that are useful to find out whether a big box contains the egg: Shaking it (if the egg is in one of the two smaller boxes contained it would sound), or opening the boxes.

Test phase. The experimenter hides the egg in one of the small boxes. The child is then asked to find the egg, and is told that he can open only one of the big boxes.

We look at whether children will perform different actions depending on the condition they are assigned to. Namely, we expect more children to shake the big boxes first in the uniform condition as compared to the skewed condition. Indeed, in the uniform condition children don’t know where the egg might be hidden, so it makes sense to shake the boxes first to find out which one contains the egg, and then open that box (remember that children are told that only one box can be opened). In the skewed condition it might make more sense to open the box where the experimenter has always hid the egg during training, without wasting time shaking the boxes.

Current and Future Directions

To better understand how children decide which learning strategy to implement depending on the information structure of the task at hand, we are currently developing various heuristic models of adaptive strategy selection that take into account both individual differences in cognitive capacities, such as memory and perception, and socio/cultural/educational factors. This broad perspective will help identify the factors responsible for developmental differences in ecological learning.